On the outbreak of war there were about 643,000 women in the paid workforce. Most were either single women, widows, or deserted wives, since married women were expected to be supported by their husbands. Pay rates reflected this general assumption. From the first minimum wage decision by Justice H.B. Higgins of Australia’s Conciliation and Arbitration Court, in the famous Harvester Judgement (1907), a man’s pay was set at a rate deemed to be sufficient to house, feed and clothe a family of five, including a wife and three children. This principle endured for the next 70 years. Women’s pay rates were generally set at between 50 and 54 per cent of the male rate, since they were assumed to be dependants. It was a system that took no account of the actual family responsibilities of many women and meant that it was almost impossible for a woman to support a family on her own wage alone.

A highly segregated workforce reflected this principle, with rates of pay in so-called ‘women’s industries’ generally set at about half the rate applied to ‘male’ industries. In 1939 many essential wartime industries, like munitions or heavy industry, were staffed almost entirely by men, and the wages were set at men’s rates. As the numbers enlisting in active service grew, those industries faced severe workforce shortages. However many other equally essential wartime industries, like the food and clothing industries, traditionally employed women – at lower rates of pay. These inequalities continued throughout the war years and they extended to white collar work, where the tasks performed might be exactly the same. Female clerks and teachers for example, were paid substantially less than their male counterparts.

The question of equal pay

Women’s groups first advocated for equal pay in the early years of the twentieth century, but it was not until the late 1930s that a formal organisation was created to press for reform. The Council of Action for Equal Pay (CAEP) was active from 1937-1946, headed by two redoubtable socialist feminists, Muriel Heagney and Jessie Street. Although the CAEP was based in Sydney, Heagney was a Victorian socialist and trade unionist who had worked in Melbourne for much of her life. She was a life-long advocate for women’s advancement and for equal pay specifically.

As pressure on the workforce grew during the early war years, both government and the trade union movement began to consider the issue of differential pay rates. Estimates of the labour shortfall varied, but some suggested that as many as 50,000 additional workers were needed in the services, munitions and aircraft production. It was obvious that women workers would have to be recruited and that low pay rates might be a deterrent. Some unions already supported the principle of equal pay, even if only as a defensive measure to protect men’s jobs. In April 1941 a conference of the Australasian Council of Trade Unions adopted a motion in favour of equal pay. The motion read:

The conference affirms the right of women to earn their living in industry, the professions and the public service and demands for all workers the legal right to equal occupational rates based on the nature of the job and not the sex of the workers.

It was an important statement by the membership at the conference, but it was a view opposed by the powerful executive of the Australian Council of Trade Unions.

As employment pressure grew during 1941 the Australian Government debated what to do. Under wartime regulations government had the power to legislate for equal pay. This course was taken later in the war in both the United Kingdom and the United States, but Labor Prime Minister John Curtin chose instead to negotiate a compromise position with the ACTU and with employers. In October 1941 his government announced its support for the recruitment of women workers into industries formerly reserved for men, but made it clear that this was a temporary measure. In a famous statement, he announced that these women would be employed only ‘for the duration of the war’.

All women employed under the conditions approved shall be employed only for the duration of the war and shall be replaced by men as they become available.

The stage was set for women’s recruitment, but only as a wartime measure.

The Women’s Employment Board

To deal with the thorny issue of pay rates for women workers government created a separate tribunal, the Women’s Employment Board (WEB), in March 1942 with a brief to rule on wages and conditions for women working in jobs for which no female provision existed. The WEB had the power to set female rates at between 60 and 100 per cent of the equivalent male rate, but very few rulings of 100 per cent were ever made. Most were set at between 75 and 90 per cent.

The Women’s Employment Board had a short and difficult life. Its rulings were opposed by many employers, especially in Melbourne, where the Associated Chamber of Manufacturers was implacably opposed. The WEB faced repeated court challenges to its validity until late in 1944, when its functions were finally transferred back to the Arbitration Court. Historians have continued to debate the longer term impact of the WEB. Its powers never extended to the bulk of women workers, who continued to be employed in traditional female industries at low rates of pay, but during its brief existence, it still delivered pay increases to between 80,000 and 90,000 women workers, many of whom earned decent wages for the first time in their lives. Arguably it was the standard set by the WEB during the war that prepared the way for post-war wage reform for women.

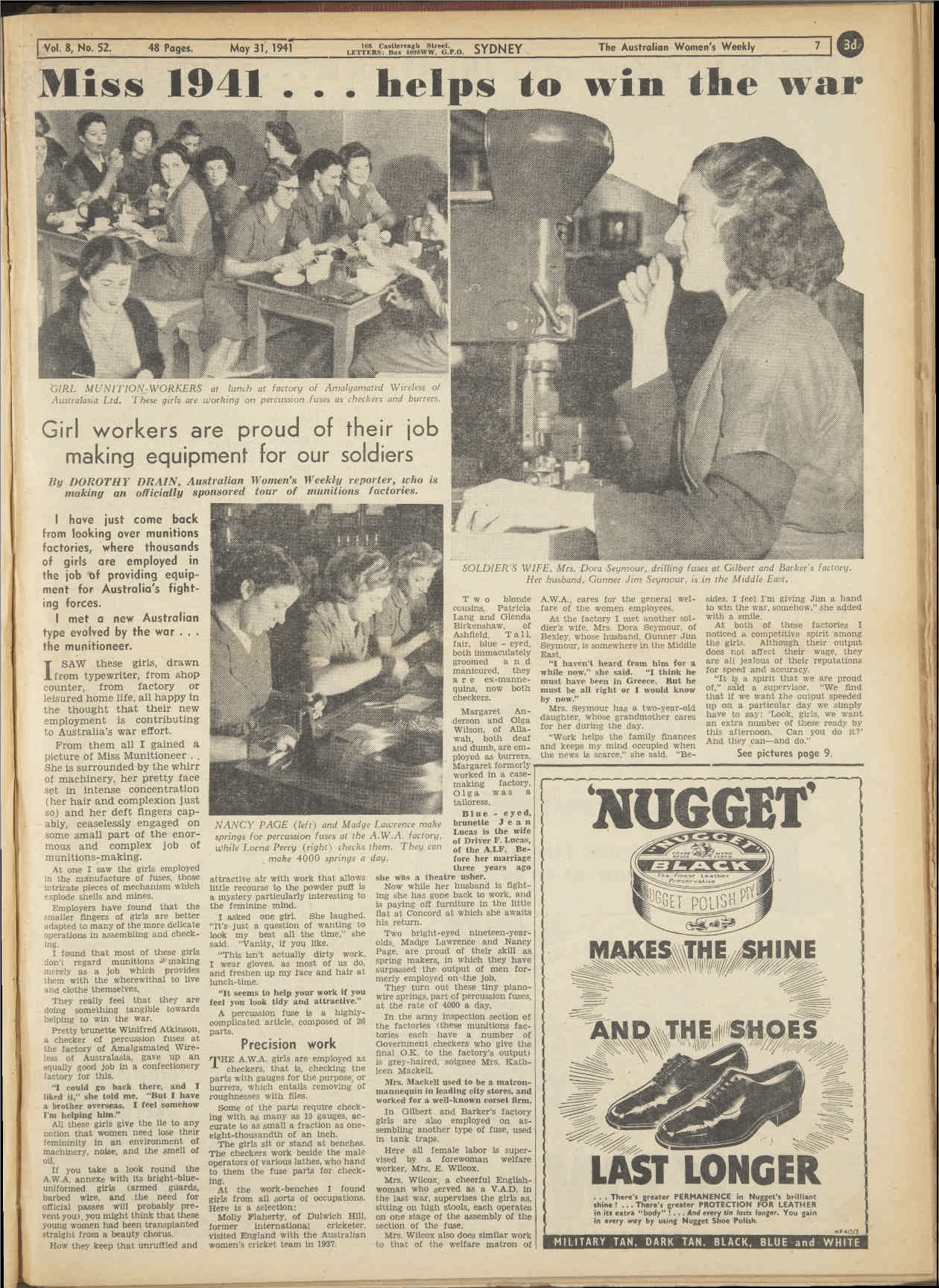

Feature article by Dorothy Drain, Australian Women’s Weekly, 31 May 1941

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Feature writer Dorothy Drain was a long-time journalist with the Australian Women’s Weekly. During the war she wrote many features on wartime activities and in 1946 travelled overseas to report on the Australian occupation of Japan. In this early piece on the work of munitions workers, Drain suggested that wartime had created a ‘new Australian type…the munitioneer’. She went on to describe these ‘girl workers’ in terminology common at the time, emphasizing both their capacity for precision work and their careful grooming.

From them all I gained a picture of Miss Munitioneer…she is surrounded by the whirr of machinery, her pretty face set in intense concentration (her hair and complexion just so) and her deft fingers capably, ceaselessly engaged on some small part of the enormous and complex job of munitions-making. …

All these girls give the lie to any notion that women need lose their femininity in an environment of machinery, noise and the smell of oil.

It is interesting that this article repeats the assumption that most working women were single ‘girls’, though one of the women pictured in the article was identified as the wife of a serviceman.

Article printed in the Argus 27 September 1944

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Another article published in the South Australian newspaper, the Mail, claimed that only one man was employed at this factory ‘to do the heavy lifting work and he also makes tea for the women employees’ – a nice ironic point! 7 October 1944, p.9.

Other essential industries

While some women benefited from the higher wages awarded by the Women’s Employment Board during the war, those who worked in other essential wartime industries (the vast majority) did not. These were women whose jobs were classed as traditional ‘female’ jobs, and they included those producing the food, clothing and other goods required to equip the services. Australia, with New Zealand, accepted responsibility for feeding and clothing Allied servicemen fighting in the Pacific, as well as their own civilian populations, and this required a large boost in output from both farms and factories. Although labour was sorely needed to fill these orders, employers resisted increasing women’s wages as an inducement, despite the fact that wartime contracts were awarded on a ‘cost plus’ basis. Instead women’s wages in these industries actually stagnated for most of the war years and employers found it hard to attract workers. It was not until the last months of the war that the Australian Government acted to increase women’s wages to 75 per cent of the male rate, but only as a temporary measure. Conditions in these factories were often below standard also, as Elly Blackshaw’s memoirs confirm. Industrial action by women workers was common during the war and union membership increased sharply.

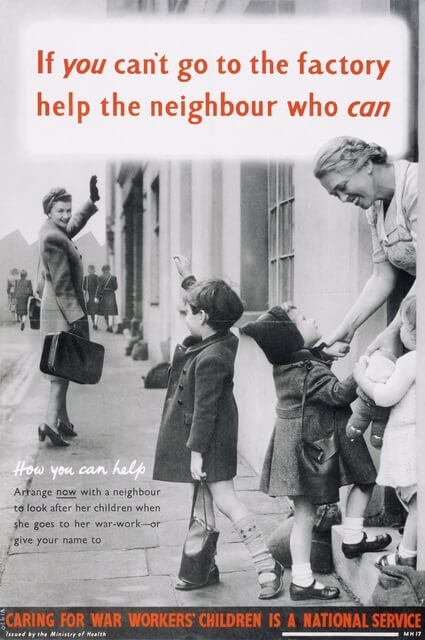

Government poster encouraging childminding

Reproduced courtesy Imperial War Memorial

Despite the urgent need for more women workers, government never considered providing child care for workers. Instead, workers were expected to make their own arrangements. Here a poster claimed: ‘Caring for war workers’ children is a national service’.

![]() Thanks girls and goodbye!

Thanks girls and goodbye!

With the end of the war came the end of opportunity for women in many industries. Returning servicemen reclaimed their jobs and women were urged to return to traditional ‘female’ jobs, or better still, to marry and have children to build up Australia’s population. Many were happy to do so, but others resented the return to poor pay and conditions.

The impetus went out of the equal pay movement for a while too. The Council for Action on Equal Pay eventually disbanded in 1948, as it failed to attract support from younger women. But all was not lost. The war had shown what women could do in the workforce. It had also broken down some of the taboos surrounding married women working. While many women did leave the workforce for marriage immediately after the war, the numbers working soon recovered to pre-war levels and beyond. By 1948 women’s employment reached the same level as that of the peak wartime year of 1943 and continued to rise. In fact from 1947-61 the female workforce increased at a faster rate than the male, although much of it still in traditional ‘female’ industries and driven by immigration.

In 1950 the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Court handed down a decision to establish the first female minimum wage, set at 75 per cent of the male rate. Although many women’s organisations were disappointed by the decision, it was at least an improvement on the existing standard, and may well have reflected the decisions of the Women’s Employment Board during the war. An active Equal Pay campaign resumed in the late 1950s, but it would be another twenty years before real progress was made.

Author: Margaret Anderson

Next page: Volunteering for Victory