Food was rationed progressively from June 1942. Butter was the first item to be rationed, as Australia struggled to meet its commitments to Britain and the troops in the Pacific. Consumption was limited to one pound (454 grams) per adult per week, reduced to eight ounces in July 1943 and six ounces in 1944. The ration in Britain at the same time was only four ounces. Housewives were advised to substitute dripping (the fat rendered from mutton or lamb) wherever possible and many children of this era were fed bread and dripping - a staple in poor diets for years. Margarine was also recommended, though many cooks disliked it.

Poster identifying food as a ‘munition of war’.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

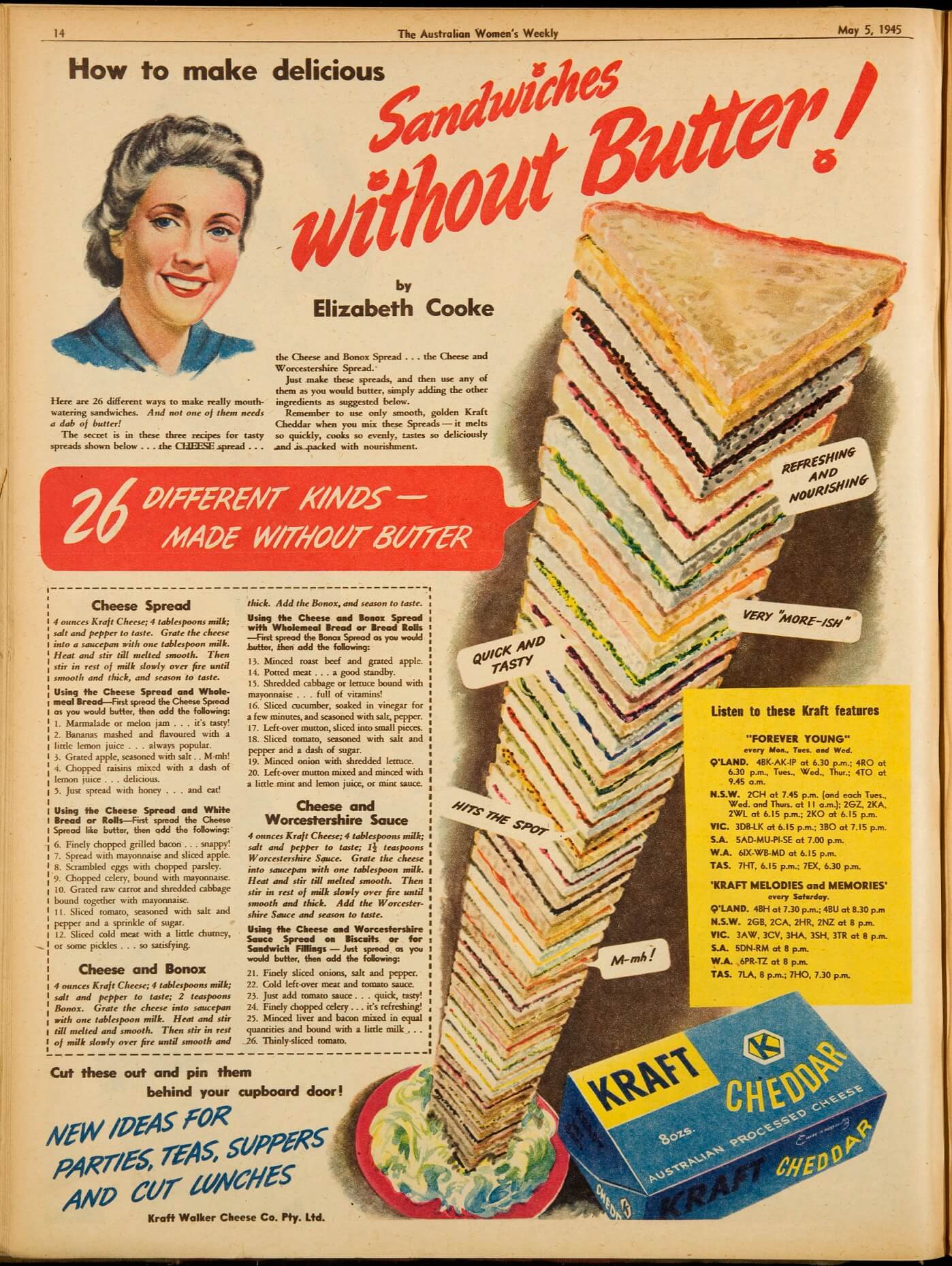

‘Sandwiches without Butter!’ Advertisement published in the Australian Women’s Weekly, 5 May 1945.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Also apparently an advertisement for Kraft cheese products!

Some of the recommended sandwiches include:

Cheese spread with grated apple and salt

Cheese spread with grilled bacon

Cheese spread with grated raw carrot and shredded cabbage, bound with mayonnaise

Cheese spread mixed with Bonox and potted meat

Cheese and Bonox spread with minced onion and lettuce

Cheese spread mixed with Worcestershire sauce and tomato sauce

Tea was the next casualty, as the Japanese advance in south-east Asia disrupted tea imports. On 3 July a ration of one half pound of tea (about 227 grams) per adult every five weeks was gazetted. It was said to allow for three cups of tea per day, which was less than most Australians normally consumed. By November the ration had been increased to the same quantity over a four-week period, on the basis that tea was a ‘necessity’. Sugar was rationed from August 1942, with an allowance of one pound of sugar (454 grams) weekly per person, thought to be about half the average weekly rate of consumption. There were additional allowances for summer preserving, though these were strongly condemned as inadequate by the Housewives’ Association and those middle-class housewives with fruit gardens. By the middle years of the war eggs were also in short supply and in February 1945 Egg Priority Cards were issued to young children, invalids, nursing and expectant mothers. Others made do without – a great inconvenience to cake makers.

A crowd of people at a city butcher shop, Melbourne, 1944.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Along with rationing of tobacco and petrol, meat rationing was the most unpopular with the Australian public.

Meat was not rationed until relatively late in the war, in January 1944, and was very unpopular, not least because of the complicated ration system involved. More expensive cuts of meat required additional coupons, prompting many complaints from people in more prosperous suburbs who were used to eating the better cuts of meat. The initial ration allowed for 2.25 pounds of meat (just over one kilogram) per adult per week, reduced by the end of the war to just over two pounds, but this only applied to red meat. Sausages, poultry, rabbits, offal, fish, bacon and other processed meats were not rationed. Once again it is likely that poorer families ate far more meat during the war than before. Fruit and vegetables were not rationed, but there were periodic price hikes and many shortages. Australians were urged to plant vegetable gardens in any available plots of land, and many did.

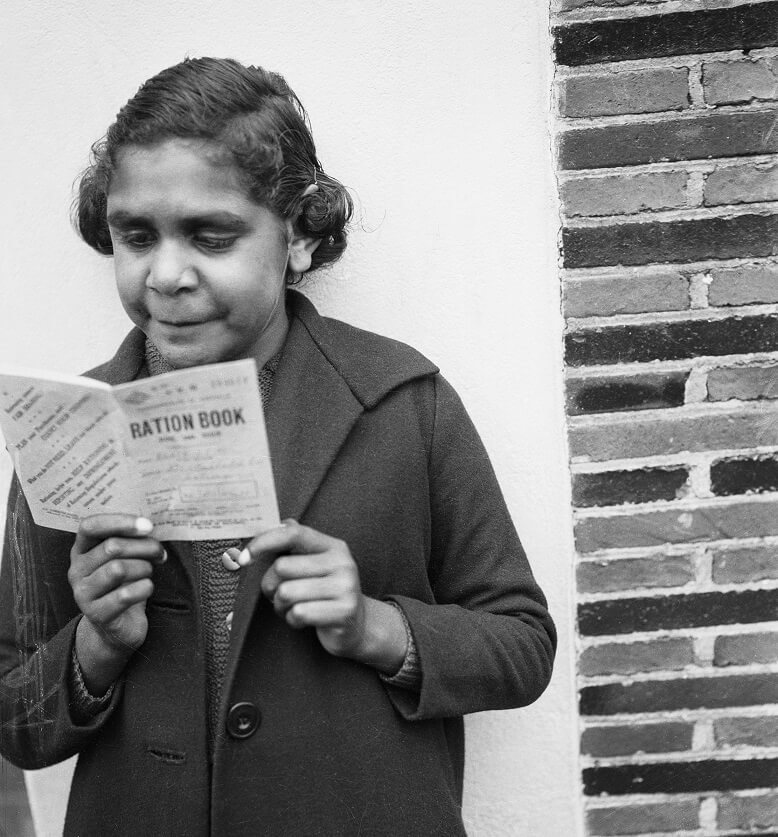

An unnamed First Nations woman studying her new ration book at an issuing centre in the Brunswick Town Hall, 1943.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Little has been written about the impact of wartime conditions on local First Nations people, but it is likely that the rationing system enabled many families to eat better than they had before.

The shortages and the rationing continued after the end of the war, longer for some items than for others. Although the restrictions did not last as long as those in Britain, Australians were very weary of rationing by the time it ended. Tea and butter rationing continued until 1950, although rationing of other items ended earlier, from 1947.

Cooking for Victory

Managing ration coupons, and finding substitutes for scarce household items, made the job of the housewife much more difficult. Government recognised this challenge in propaganda posters that highlighted the central role of the thrifty home manager in contributing to the war effort.

Propaganda advertisement addressing ‘Mrs Housewife’, Argus, 7 December 1943

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Posters and advertisements like this acknowledged the role of the woman at home and also gave practical examples of what could be done. In this case growing vegetables in home gardens and keeping chickens in backyards was suggested.

The patriotic housewife had no shortage of advice: women’s magazines, the Housewives’ Association and local newspapers all offered helpful hints on ways she might economise. Recipes began to appear for cakes or sandwiches made without butter or eggs, and for meat-free meals, while special ‘austerity’ cookbooks were printed. Magazines like the Australian Women’s Weekly offered prizes for the most economical recipes, and shared tips on useful substitute ingredients. But some shortages hit hard. Complaints about the meat and butter rations were common, while the sugar ration attracted the ire of organisations like the Housewives’ Association. The Housewives’ Association had lobbied to be represented on the government’s Rationing Commission without success and resented its exclusion from this powerful body.