Of course it is the function of man to go to war. It is his function to report war. Woman has always had the less picturesque job of remaining at home and doing the worrying. So in sending Mrs Shelton Smith to Malaya, the Australian Women’s Weekly has not only made newspaper history, but has broken down a convention that has persisted through the ages – that a woman can’t do the “tough” jobs of journalism – that she is too ‘soft’

- Alice Jackson, Editor of The Australian Women’s Weekly, 1941

World War II provided opportunities for women beyond the factory floor. By 1941, the ABC employed 19 women as announcers, and over 20 women were accredited war correspondents. They did not, however, report on action at the front: they were expected to provide ‘human interest’ stories.

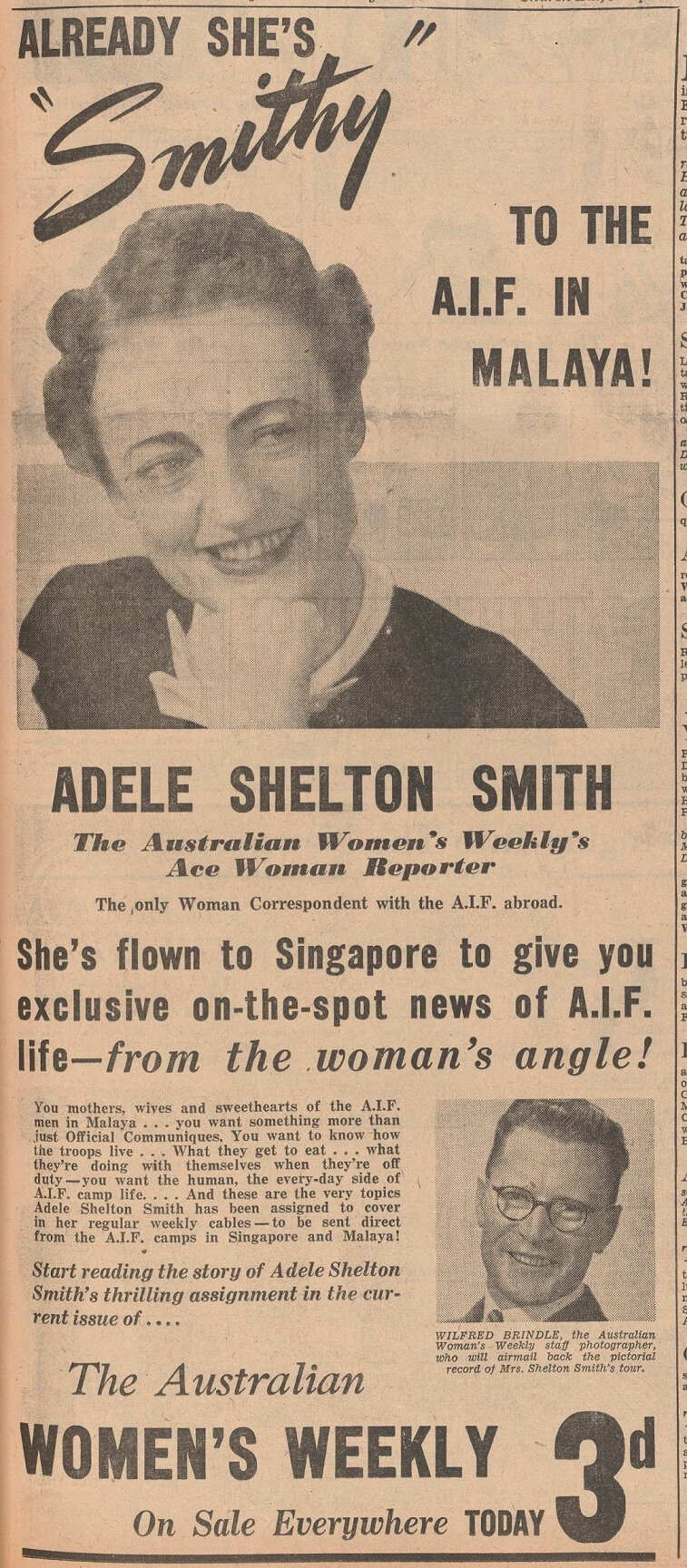

Melbourne journalist Adele ‘Tilly’ Shelton-Smith was the first woman to travel from Australia to report from an overseas military theatre. She went with a photographer to Malaya in 1941, representing The Australian Women's Weekly. Banned from writing military articles, Shelton-Smith wrote about daily life instead - the soldiers’ ‘healthy meals’, the weather, and their living quarters, which she described as ‘more comfortable than home’. She wrote about the soldiers’ leisure activities, their ‘good cheer and comfort’, and reported that they even had time to relax - a photograph taken by the photographer, Bill Brindle, showed a soldier in close embrace with a Chinese taxi dancer. (Taxi dancers were paid dance partners.)

Back in Australia, wives and mothers were horrified – and angry! Was Shelton-Smith suggesting their husbands were cheating, or was she simply insulting their reputation? The Australian tabloid press weighed in, furious that she had ‘glamourised’ the troops’ role in Malaya. Given the welcome later offered to American servicemen in Melbourne, it was all a bit hypocritical.

Bill Brindle and Adele ‘Tilly’ Shelton-Smith leaving for Malaya in March 1941, published in The Australian Women’s Weekly, 29 March 1941.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The soldiers themselves were far from impressed. One officer wrote to his wife: ‘If ever the lads here get their hands on that damn fool woman they will tear her limb from limb’. A cartoon by Private Stan McAlister published in the 2/19th Battalion newspaper, Nineteenth, showed a scantily-clad Shelton-Smith being pursued and then strangled by an Australian soldier.

Why was Shelton-Smith the target of such vehement animosity? Historian Jeannine Baker argues that Shelton-Smith ‘inadvertently transgressed the code of Australian manhood’. Her reports of camp life in Malaya ‘feminised and emasculated the soldiers, and contradicted the military’s image of them as exemplars of the Anzac legend.’ She suggests that the soldiers’ hostility was perhaps compounded by their inaction in Malaya, and by their perception they were being unfavourably compared with other Australian troops actively engaged in battles overseas.

According to Baker, the content of Shelton-Smith’s articles had ramifications for future Australian war reporters. The military became even more wary of women reporters, and their work was tightly managed and controlled. This relaxed a little towards the end of the war. Reporters such as Lorraine Stumm, Iris Dexter, Alice Jackson and Dorothy Drain proved they were capable of giving more than just the ‘woman’s angle’. In fact, Stumm was the first Australian woman to witness the aftermath of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. She was amongst a small party of journalists flown over the destroyed Japanese cities. And she got the scoop. Stumm interviewed the first known European survivor, Jesuit priest Wilhelm Kleinsorge, who gave this description of the carnage:

People were wandering about with their whole faces one large blister from the searing effect of the bomb. Only forty out of six hundred schoolgirls at the Methodist College survived. Three hundred little girls at the government school were killed instantly. Thousands of young soldiers in training at barracks were slaughtered. I walked for two hours and only saw two hundred people alive.

Shelton-Smith was devastated by the attacks on her, but continued to support and report about the Australian troops. She visited the troops stationed in Darwin in July 1941, and wrote again about the troops in Malaya in December 1941 – albeit a little differently this time. According to Baker:

Shelton-Smith’s stirring, patriotic article about the 8th Division troops – the final text and appearance over which she would have had some control – was filled with images of ‘tough, ready’ men who ‘fight like jungle tigers’, and in contrast to her previous articles, included vivid descriptions of jungle training. The troops, she wrote, ‘cut their way through the jungle with native parongs, raked the jungle floor for scorpions before lying down to sleep in their sweaty clothes, slept in torrential rain [and] lived on a handful of rice a day’.

Sources:

Online

Journals

Baker, Jeannine Ann 2013, ‘Beyond the ‘woman’s angle’: Australian women war reporters during World War II’, PhD Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Author: Old Treasury Building