The following content has been approved by the Wurundjeri Woi wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation.

Cultural warning: this page contains material that refers to deceased persons, and colonial records using language now considered offensive. They are included here as historical evidence.

FIRST PEOPLES

The place we know as Melbourne is part of the country claimed by the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung Nations. The Woi wurrung Nation consists of the land of the Yarra drainage basin. The clans who dwelt along the river near the site of Melbourne are known as the Wurundjeri people. The Boon wurrung people occupied the land around Port Phillip Bay on the southern banks of the river. Both groups share a common language and culture with three other groups: the Watha wurrung, Daung wurrung and Dja Dja wurrung, which together form the Kulin Nation.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the people of the Kulin Nation would meet regularly near the river for ceremonies, inter-Kulin business and politics. Complex protocols surrounded access to territory and resources, none of which early Europeans understood.

Land and people

The Kulin saw the land and the people as one continuum. Wurundjeri people called their river Birrarung, meaning ‘river of mists’, and it was central to their livelihood, their cultural life and their identity. They took their name from one of the trees that grew along the river –‘wurun’ or manna gum, and ‘djeri’, a grub found in or near the tree. Colonists called the Wurundjeri the ‘Yarra Tribe’.

Creation stories

Creation stories reflected the interrelation between land and people. The Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung shared belief in a powerful spirit-ancestor, Bunjil the eagle. Stories featuring Bunjil both explained the creation of the land, and provided guidance for social behaviour.

The Wurundjeri lived in camps along Birrarung, in small huts or mia mias made of bark. William Thomas, Assistant Protector of Aborigines, reported seeing ‘in half an hour a village comfortably housed... A few sheets of bark with a sapling, and two forked sticks make at once a habitation…’

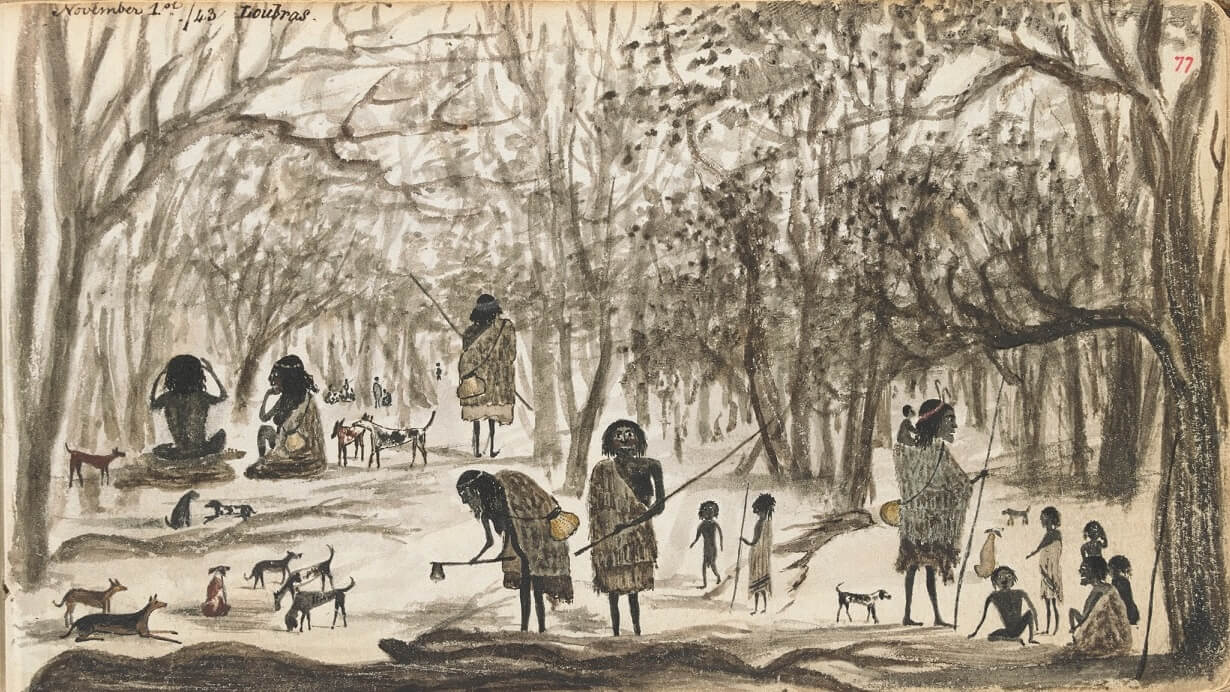

John Cotton, Aboriginal camp on the banks of the Yarra, c.1845

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The woman shown here wears a possum-skin cloak. About eighteen skins were needed to make a cloak.

One Boon wurrung story explained the formation of the river and the creation of Port Phillip Bay in what was once dry land. In this story Bunjil told two young companions to empty out two water containers onto the ground. The water formed a great flood that created Birrarung and Port Phillip Bay.

The Woi wurrung leader Beruk Barak (William Barak) told a different story:

Two boys were playing when one of them climbed a wattle tree to find wattle-gum. He began throwing lumps of gum down to the other boy, but they disappeared. The boy noticed a hole in the ground and poked his spear into it in search of his gum. An old man sleeping beneath the ground woke up very angry and carried off the frightened boy.

The path he made became the river. When Bunjil heard the boy’s cries, he threw sharp stones in the path of the old man, causing him to fall and cut himself badly. The boy escaped and ran home. Bunjil appeared before the old man and said: ‘Let this be a lesson to all old men. They must be good to little children.

LIVING WITH THE LAND

Wurundjeri people knew their land intimately and moved through it with the seasons. They lived lightly from the land, husbanding its resources. In the summer they camped along the banks of Birrarung and its tributaries, then moved inland to the Dandenong Ranges as the days shortened.

Summer along the river

Summer was a time of abundance. Popular camping places included what is now the Domain, both sides of the river near Yarra Park and the Royal Botanic Gardens. From there the men hunted kangaroo, possum, emu, bandicoot and brush turkey. The extensive wetlands provided fish, eels and shellfish, as well as snakes, water rats, frogs and platypus. Fish was an important part of their diet. Men fished from bark canoes, cut and shaped from the river red gums; or speared fish from the riverbanks. They trapped eels in stone traps, and traps woven from rushes. Birds and birds’ eggs were also eaten.

Women also hunted for small animals and gathered edible plants and berries, providing up to 60 per cent of the clan’s diet. Especially important were the roots of various plants, including the tubers of the murnong (yam daisy). Other plants provided medicines, fibre for weaving and utensils. They made clothing from animal skins, stitched together with animal sinew. Possum-skin cloaks were especially prized for their warmth.

Henry Godfrey, Loubras, November 1st 1843

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

First Nations women gathering murnong (yam daisy).

Winter

As the days shortened the Wurundjeri moved inland, following pathways along the rivers and valleys in use for generations. They timed their arrival at points along the way to coincide with natural opportunities, like the migration of mature eels downstream to breed in salt water. The extensive wetland called Bolin was a fine location for eel fishing at this time.

The forests of the Dandenong Ranges provided shelter and firewood during the colder months.

INVASION

Naming the river

The Yarra got its name by mistake. John Wedge, surveyor for Batman’s party, first recorded the name ‘Yarrow Yarrow’ in his notebook. Later he admitted that he had mistaken the Kulin name for the falls, or rapids, for the name of the river itself, but by then the name had stuck.

A town by the ‘Falls’

A tiny village, still known only as ‘the Settlement’, grew up on the northern side of the Yarra near the ‘Falls’. This site became Melbourne’s principal landing place, with direct access to the main streets and the Customs House. The river connected with the bay anchorage, initially at Williamstown and then Sandridge (Port Melbourne). In 1837 Surveyor Robert Hoddle pegged his city grid in alignment with the river.

‘...perhaps the finest river I have seen in New South Wales’

Governor Sir Richard Bourke

Early European observers admired the beauty of the Yarra and marvelled at its plentiful fish and fowl. But within a decade they had cleared its banks of trees and polluted its pristine waters. And this was only the beginning.

Robert Russell, Melbourne from the falls, 30 June 1837

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The Woi wurrung people from north of the river and the Boon wurrung from the south used the ‘Falls’ as a crossing point, and a place to trap migrating fish. When Charles Grimes and his party ventured up the Yarra in 1803 they observed ‘native huts’, a canoe, and a bar across the river used for fishing.

The first European arrivals settled on the north side of the Yarra near the ‘Falls’, a low rocky ledge across the river opposite today’s Market Street.

The wind south this morning... The Boat went up the large River I have spoken of which comes from the East and I am glad to state about six miles up found the River all good water and very deep.

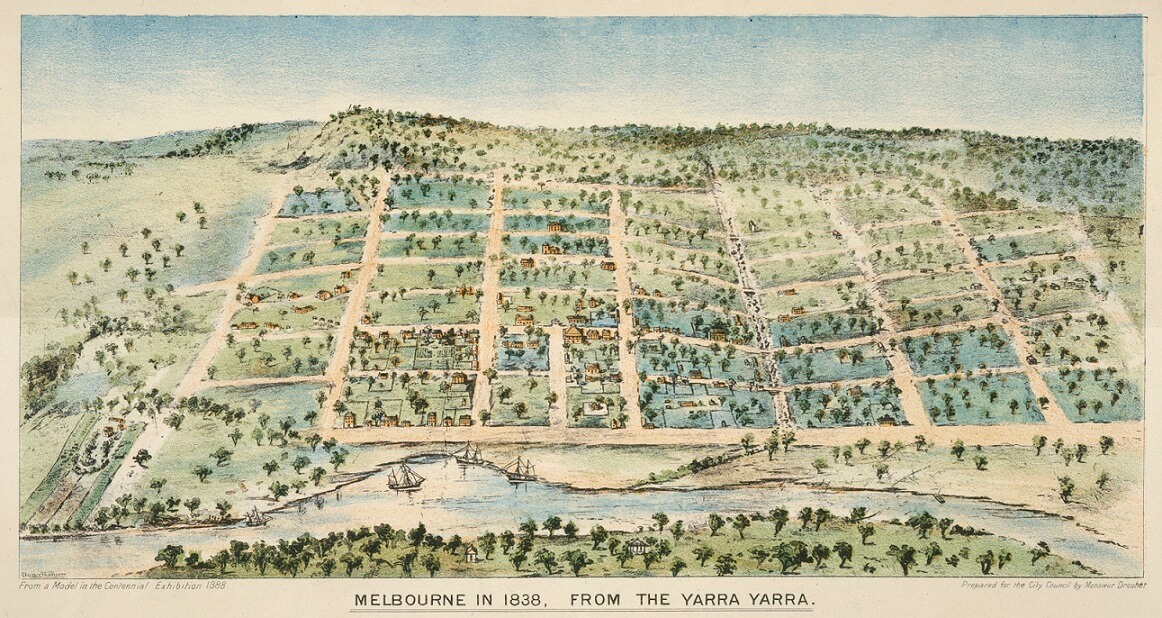

Within only three years of European settlement, Melbourne had grown to encompass much of the lower Yarra River.

Melbourne in 1838, from the Yarra Yarra, by Clarence Woodhouse, 1888

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Batman ‘Treaty’

John Batman was a clever and determined capitalist. He knew that the British Government opposed further settlement in Australia, because of its impact on First Nations People. He came to Kulin land with a treaty already prepared and sat down with Elders of the Kulin Nation. Billibellary was one of the Elders present. William Barak may have observed as a ten year-old boy.

Batman claimed 600,000 square acres of country in his treaty, in exchange for blankets, steel blades, mirrors and a yearly tribute. The meaning of his ‘treaty’ has been debated ever since. It is possible that the Kulin saw value in an alliance with the newcomers. Batman had also shown respect by appearing to ask for permission to enter their country and taking part in ceremonies of welcome. It is most unlikely that the Kulin foresaw a permanent occupation. The British Government disallowed the treaty immediately, but only to claim the land on behalf of the Crown.

Batman’s treaty with the aborigines at Merri Creek, 6th June 1835, by John Wesley Burtt, c.1888

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

A depiction of Batman’s meeting with the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung people. This painting shows some of the items Batman offered to the Kulin, including mirrors, shirts and beads - a token payment for an enormous stretch of valuable land.

This image was created more than forty years after the event. There were no images of Batman created while he was alive, so we don’t know what he actually looked like.

The river flats and lagoons of Birrarung were favoured places for the Wurundjeri people, providing fish, eels and birds’ eggs. Canoes were made from the bark of the river red gum. The bark was removed in large sheets then placed over fire to make it pliable.

DISPOSSESSION

The entire country of the Waworong [Woi wurrung]… is now sold or occupied by squatters... The very spots most valuable to the Aborigines for their productiveness – the creeks, water courses, and rivers – are the first to be occupied.

Assistant Protector E.S. Parker to Chief Protector Robinson, 1 April 1840

‘Blackfellows all about say that no good have them Pickaninneys now,

no country for blackfellows like long time ago.’

Billibellary, Ngurungaeta (leader) of the Wurundjeri people

The impact of European occupation on First Nations people in Victoria was swift and devastating. They suffered loss of land, loss of food, loss of culture and ultimately loss of life. Estimates suggest that in less than two decades Kulin people declined in number by more than 80 per cent.

Frontier violence

As the frontier moved out from Melbourne the cumulative impact of European settlement became more severe. Watercourses were appropriated first. Food quickly became scarce, and the Kulin naturally looked for reciprocal access to the introduced cattle and sheep that were destroying their gathering sites. Violent clashes and brutal reprisals followed.

At the same time, introduced disease took its lethal toll. Smallpox, measles, pneumonia and bronchitis decimated communities. Birth rates plummeted as the Kulin reflected sadly on their loss of land and culture.

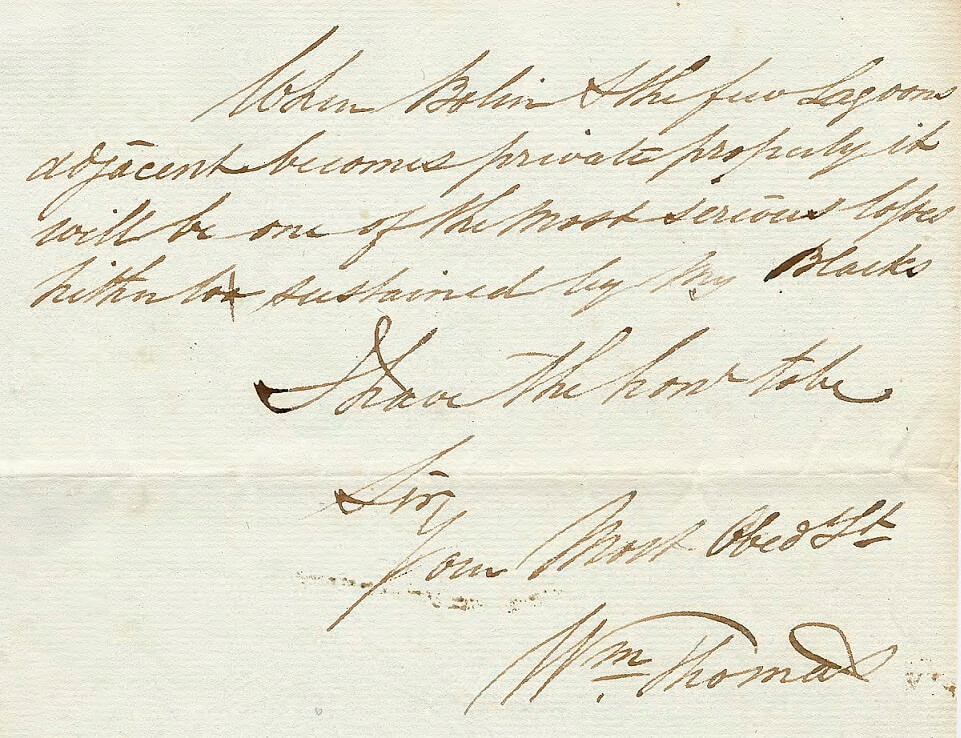

I could not but feel for the poor blacks. They had till this visit an undisturbed range among the lagoons… now… the Yarra is forever closed to them.

William Thomas, correspondence, 12 March 1841

The Bolin Lagoon (or Bolin Bolin Billabong) was a place of great significance to the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung people. They camped at several sites around the lagoon and curve of the Yarra River, on the north and south sides. Eels were an important food resource here. According to William Thomas the Bolin lagoon ‘supported the Yarra blacks from its abounding eels one month in the year’.

William Thomas, correspondence, 12 March 1841

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria. VPRS 11, P0, unit 7, item 375

In this report Thomas describes the proposed sale of land on the north side of Bolin lagoon in March 1841 as ‘one of the most serious losses hitherto sustained by the Blacks’.

IN THE NAME OF PROTECTION

It be one of your most important duties to protect the Aboriginal natives of the district from any manner of wrong, and to endeavour to conciliate them by kind treatment and presents assuring that this government is most anxious to maintain a friendly intercourse with them and to improve by all practical means their moral and social condition… they must consider themselves subject to the laws of England.

Governor Bourke to George Langhorne, Episcopal missionary, 1837

While the Victorian colonial enterprise depended on the dispossession of the Kulin, official government rhetoric spoke instead of ‘protection’, ‘improvement’ and ‘conciliation’. Colonial authorities hoped for the conversion of the Kulin to Christianity and a ‘settled’ way of life.

The First Mission

The first mission was established on the south bank of the Yarra in 1837. There George Langhorne taught reading, arithmetic and scripture to a group of Kulin boys, and farming skills to the men, in exchange for meals. His pupils learned easily, but attendance was irregular and demand for land near the settlement soon saw the mission closed. This was to be a common pattern for land set aside for missions and reserves.

The Aboriginal Protectorate

The damning report of a British Select Committee on the impact of British settlement recommended that ‘Protectors of Aborigines’ be appointed in Australia. The Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate was duly established, with four assistant protectors under Chief Protector G.A Robinson (formerly of Tasmania). Reserve sites, intended as ‘permanent homes’ for the Kulin, were allocated to each protector. Assistant Protector William Thomas used the Merri Creek Aboriginal School as a makeshift station.

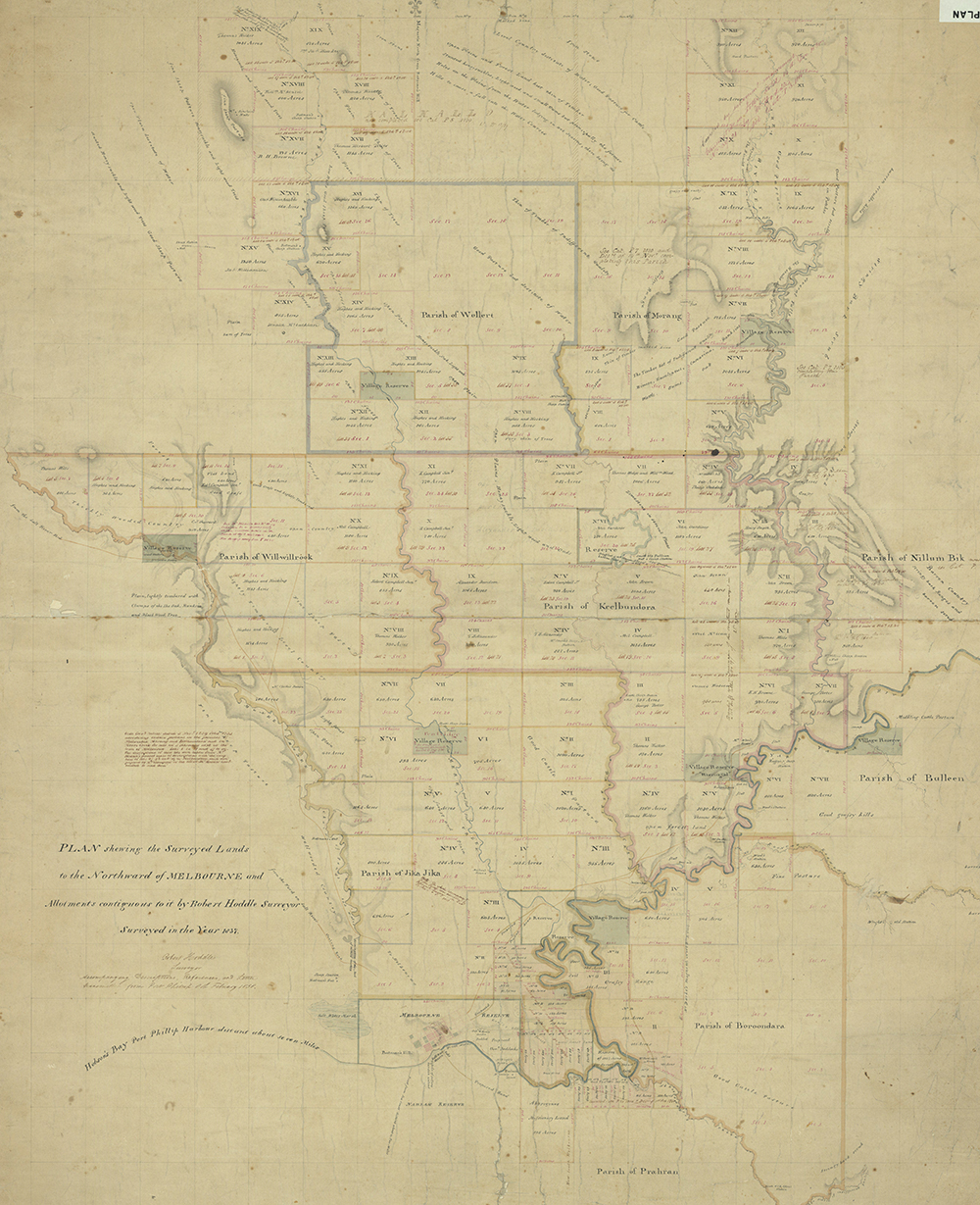

Detail from Plan shewing the Surveyed Lands to the Northward of Melbourne, surveyed by Robert Hoddle, 1837

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 8168/P2, unit 5502

Shows the 895 acres reserved for Langhorne’s Aboriginal Mission on the south bank of the Yarra River, now part of the Royal Botanic Gardens. The area was well-chosen taking in a large wetland, rich in plant foods and wildlife.

Good intentions?

William Thomas had good intentions. He learned both the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung languages and worked closely with Woi wurrung Elder Billibellary. Thomas fought to protect the Kulin in his ‘care’ from the worst excesses of settler reprisals. But he was still a man of his time and his culture, intent on ‘civilising’ and Christianising the Kulin. When in 1840 Superintendent Charles La Trobe ordered the removal of the Kulin from the settlement of Melbourne, Thomas complied.

Creation of Reserves

Policies of exclusion and containment of the Kulin continued throughout Victoria in succeeding decades. From 1858 a Central Board for the Aborigines created a system of reserves – at Ebenezer, Lake Tyers, Framlingham, Lake Condah, Ramahyuck, Coranderrk (on the banks of the Yarra River at Healesville) and Yelta. By 1877 almost all of the surviving Kulin lived either on these reserves, or nearby.

From the late 1830s the government discouraged the Kulin from visiting Melbourne. In September 1840, Chief Protector Robinson wrote to Assistant Protector William Thomas, directing him:

... no Aboriginal Blacks of this District are to visit the Township of Melbourne under any pretext whatever, you will therefore adopt the requisite measures to prevent their so doing. During the past week the Town has been completely thronged with them and great complaints have been made in consequence.

The Yarra has played an essential part in each stage of Melbourne’s history. For the Kulin and early Europeans it provided fresh water, fish, fowl and fertile land. Later expanding port facilities connected the growing city with the rest of the world. And always it has been a place for people to gather – to meet, to discuss, to celebrate, to protest, or simply to enjoy.