Drinking the Water

Initially, the Yarra was the main source of water, for drinking and other purposes. By the 1840s water pumps were installed on the north bank and men with carts sold the water, door to door. Residents also sank wells and used tanks and barrels to collect rainwater.

But industry and human waste soon polluted the river and concern grew that Melbourne might face an outbreak of disease like cholera. An enterprising company proposed to construct Melbourne’s first major dam on the Plenty River.

Xmas 1841. How we got our water in the Pree Yan-Yeanite Era, by Robert Russell, 1881

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Yan Yean

Yan Yean Reservoir was designed by James Blackburn, an English civil engineer who arrived in Melbourne in 1849. He joined with four men to form the Melbourne Water Company, its aim to provide a ‘quality of water more abundant and better than is obtainable in almost any town in Europe.’

Work began on the reservoir in 1853, at the height of the gold rush. It was sited 183 metres above sea level with an earthen bank about 9 metres high. A single pipe fed the water to Melbourne. It took four years to construct the dam, at a cost of over £750,000. Ironically, Blackburn did not live to see the reservoir completed: he died of typhoid fever in1854.

A grand opening

The Yan Yean Reservoir was hailed as the greatest public work ever undertaken in the Colony. At a ceremony held in the Carlton Gardens in December 1857, a tap liberally sprayed those in attendance. Further catchments in forested mountain country east of Melbourne were set aside, and a network of new reservoirs completed through the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Today the Yarra River catchment area provides about 70 per cent of Melbourne’s drinking water.

Polluting the River

Nothing can be more… repulsive than the approach to Melbourne by the river Yarra… polluted by the drainage and sewage of the city and of half a dozen suburbs, [it] is as offensive to the eyes as to the sense of smell; while the malodorousness of the atmosphere is aggravated by the fumes from various noxious industries that have been established on its banks.

Andrew Garran, Picturesque Atlas of Australasia,

1886

The Yarra was vital to the emerging township, facilitating trade and immigration. But within a few short years of settlement people and industry had created a putrid, noxious waterway. A vital element for industry, the Yarra also served as the city’s unofficial sewer.

Vegetation was cleared to construct wharves and factories, causing erosion and further pollution of the river.

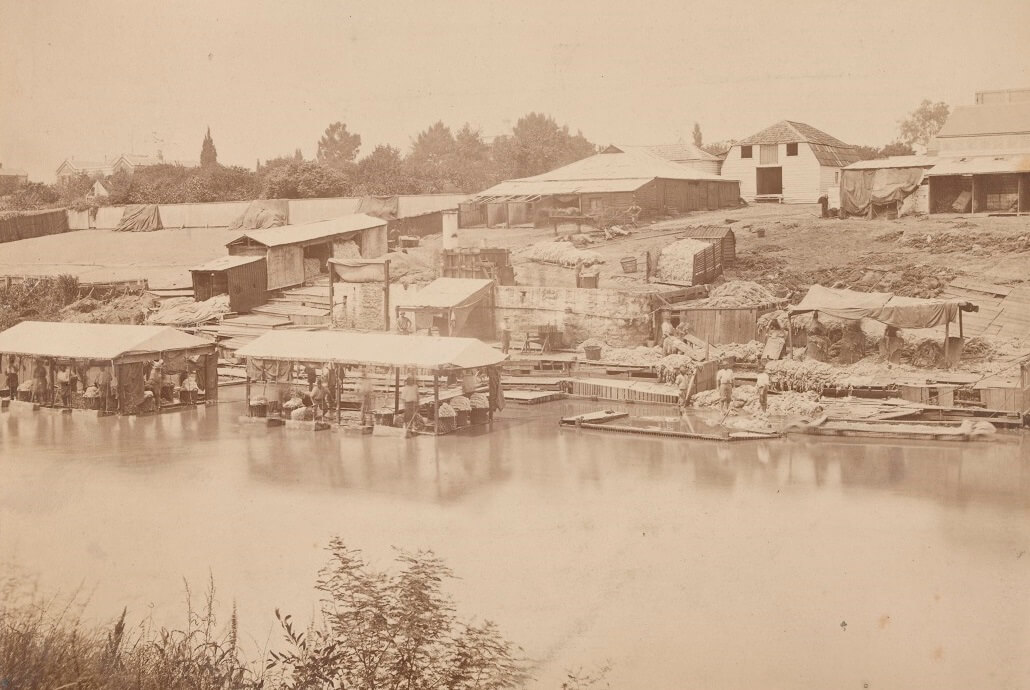

Wool washing on the Yarra, by Charles Nettleton, photographer, 1872

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Wool was washed in the river before processing into clothing, blankets and other goods. Eight or nine such works were situated on the banks of the Yarra – most were in Collingwood, upstream of the city.

Industrial waste

Noxious trades lined the lower banks of the Yarra River and upstream around Collingwood. There were slaughterhouses, tallow works, tanneries, glue works, bone mills, fellmongers, wool washers and soap works. Effluent from these sites flowed unchecked into the river. Regulations to control hygiene, offensive smells and waste disposal were elementary and poorly enforced. By the 1870s the lower reaches of the river were a stinking mess. In the 1880s the Health Committee of the City of Melbourne toured the river, shocked by what they saw. Open vats of offal, piles of drying bones and the hair and flesh from tanned hides, lay discarded in the open air. Animal carcasses floated in the water. Foul, black waste from industry poured into the river. It was a ‘state of affairs disgusting in the extreme’.

Sewage in the streets

To make matters worse, the city lacked effective drainage. Waste from homes, hospitals and stables washed into open drains and into the river. Disposing of sewage was a persistent problem. By the late 1850s ‘nightmen’ were employed to collect sewage from backyard ‘privies’, but many simply dumped their loads beside public roads or directly into the Yarra! It was not until an underground sewerage system was built in the 1890s that diseases like cholera and typhoid retreated.

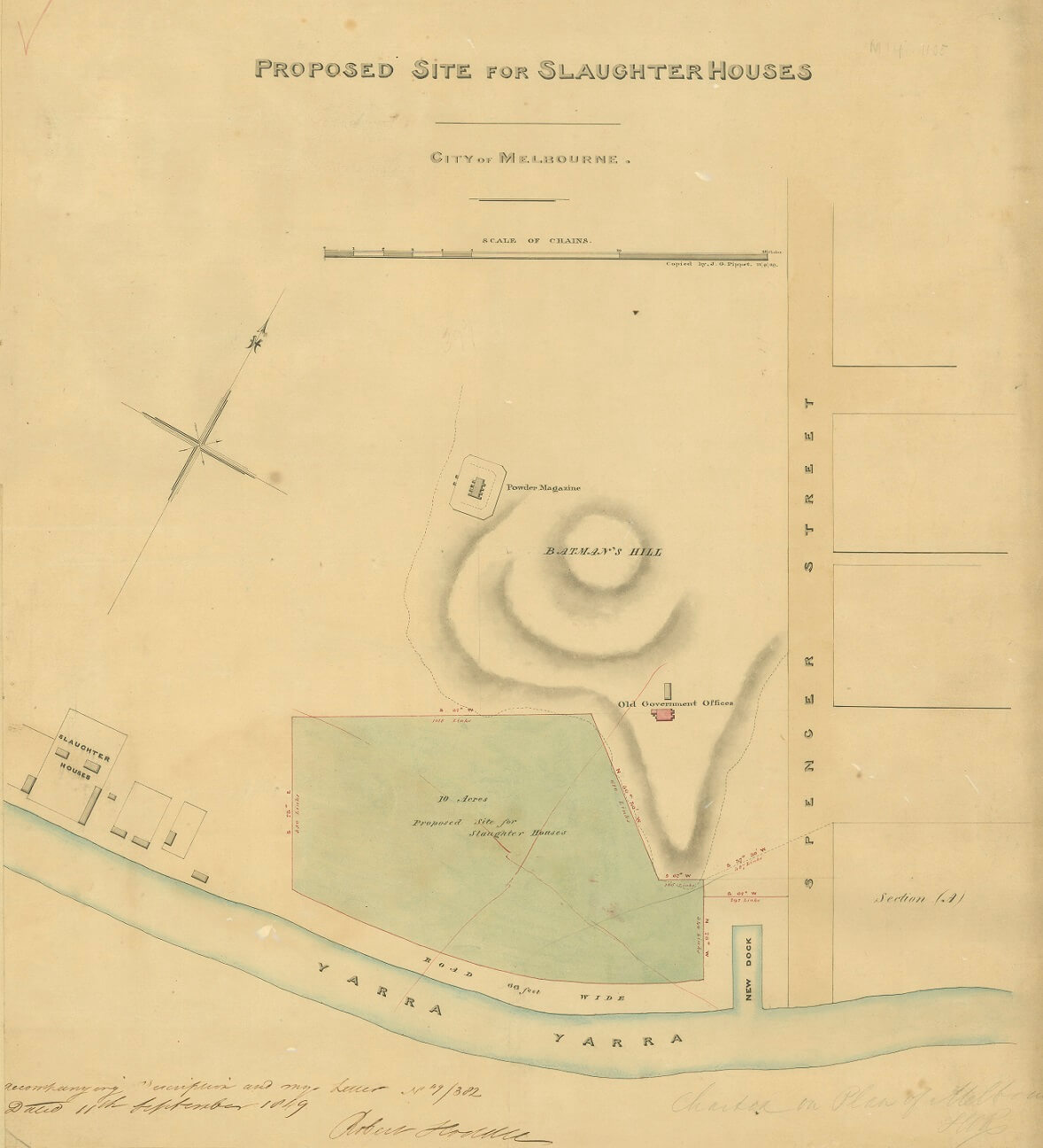

Robert Hoddle, surveyor, Proposed site for Slaughter Houses, 1849

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria. VPRS 8168, P2, Unit 51.

This slaughterhouse was planned to be located below Batman’s Hill on the Yarra.

‘The river that flows upside down’

The murky colour of the Yarra is caused by silt, dissolved from easily-eroded clay soils in the catchment area. The water was apparently clear at the time of European settlement, but intensive land clearing and development soon resulted in the presence of microscopic clay particles in the water, maintained in suspension by turbulence in the middle and lower sections of the river. When river water combines with marine salts as it enters Port Phillip, the suspended particles clump together and sink, creating layers of mud. The muddy appearance does not indicate an unclean waterway. In fact, the Yarra is now one of the cleanest rivers in a major city.

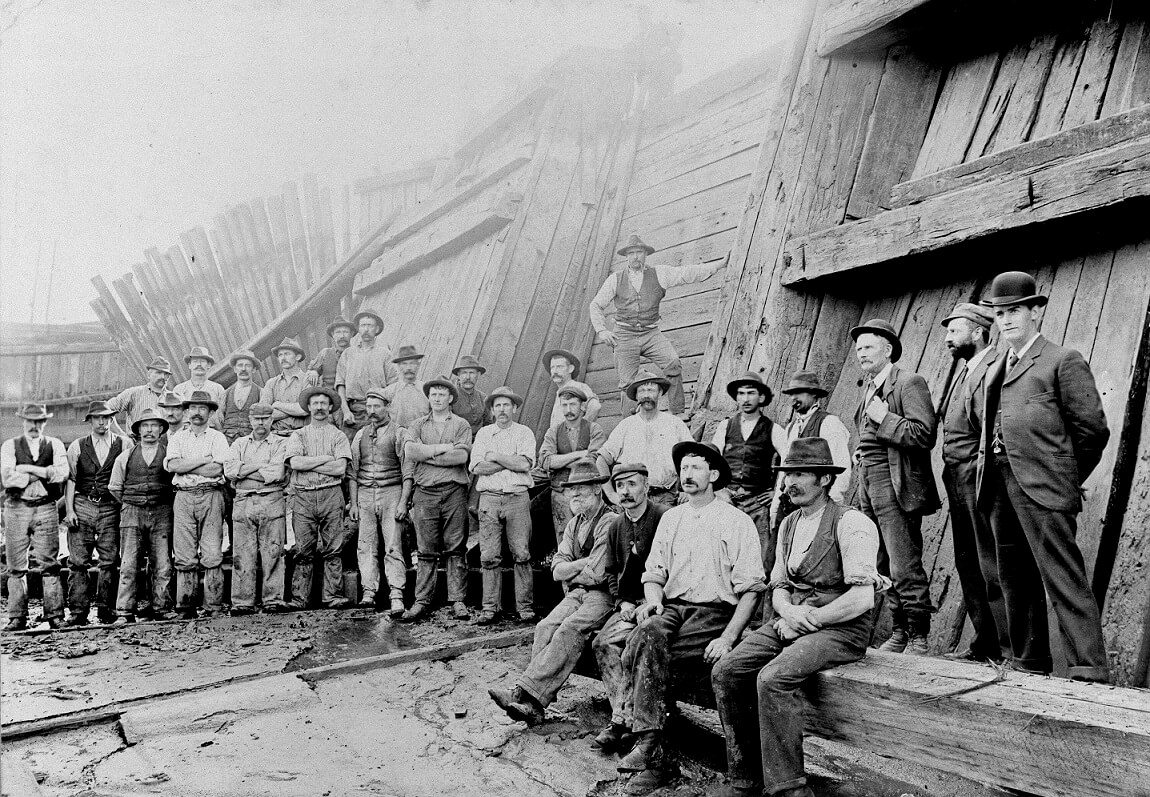

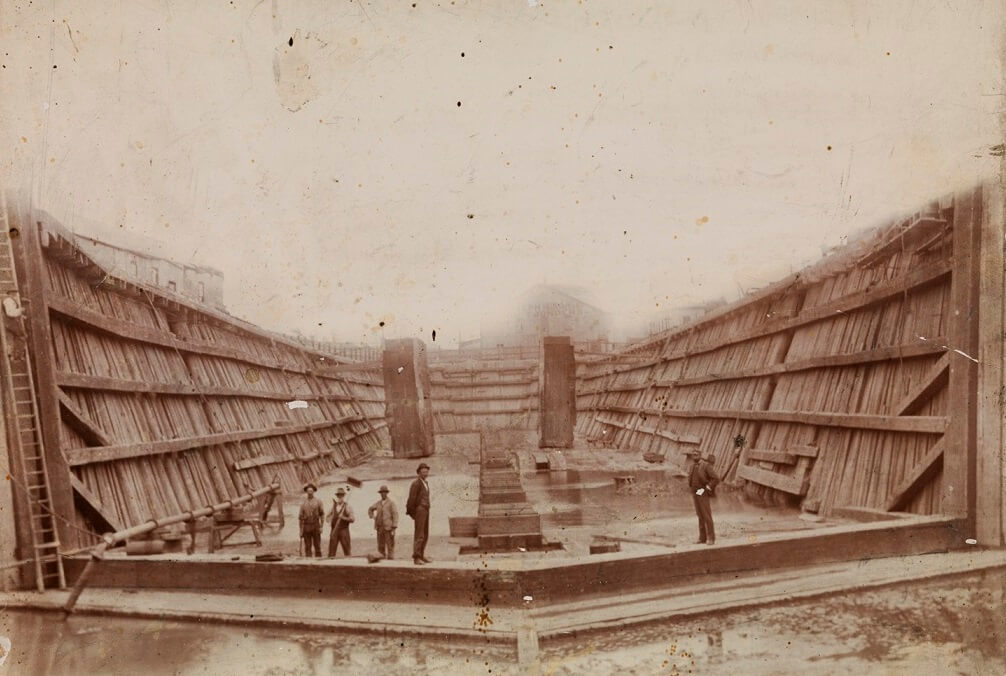

Workers at the Duke and Orr’s Amalgamated Dry Docks, c.1900

Reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

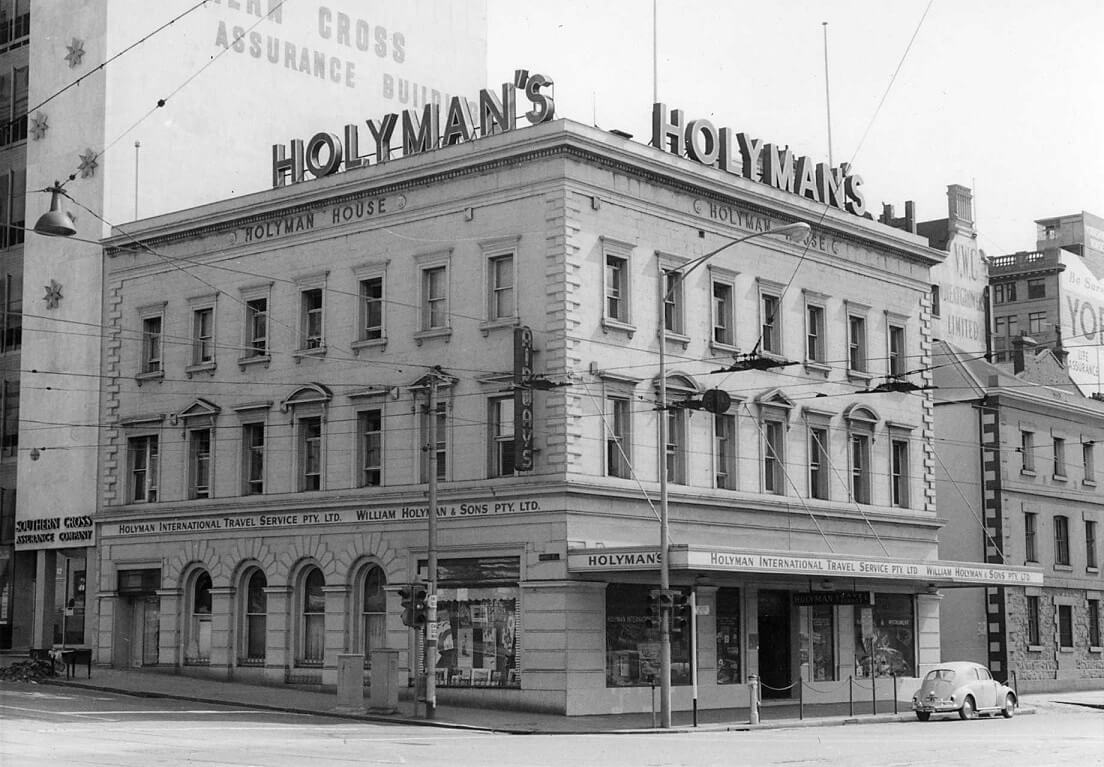

Holyman House, Flinders Street, built in 1858 for leading Melbourne wool-broker, Richard Goldsborough.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Yarra and docks west of Swanston Street were in essence the ‘lifeline’ of the city. The ports carried large quantities of primary produce (principally fine wool) for shipment to Britain. Large warehouses were built from the mid-nineteenth century. Several survive today.

Repairs to the Duke and Orr’s Amalgamated Dry Docks, c.1900

Reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

As the focal point for Melbourne’s commercial shipping trade, the south side of the Yarra was an important location for the construction and maintenance of cargo vessels.

Today the old Duke and Orr’s Dry Dock on the Yarra at South Wharf houses the barque Polly Woodside, built in 1885. Both the Polly Woodside and the Duke and Orr’s Dry Dock (built in 1875) are listed on the Victorian Heritage Register.